Learning about Movement – 2012 – Part 1

This is part 1 of a series of posts reflecting on some highlights in learning about movement that I experienced in this last year. I hope to be able to do this on an annual basis as a record of self-reflection and hopefully provide some value to others out there on the same journey.

Applied Functional Science / Chain Reaction™ Biomechanics

I have previously discussed my interest in going more in depth into multiplanar movement with my posts on 3D stretching as well as regional interdependence. I have used the FMS and SFMA off and on for a few years and felt they were both efficient and useful for their respective purposes, and I love that the research community is actively exploring the validity and reliability of these tests. I will still utilize components of these tests from time to time. However, I have personally found I need to change to a more customized approach to evaluation. In the past, I have found that in the middle of testing, I would break out of the protocols established trying to “tease” out something that did not fit cleanly into any of the tests. Part of this is just my nature, I have a difficult time adhering to standardized procedures and the way I do things just kind of evolves and varies depending by how I perceive something is presented to me. As these breakout sessions grew in complexity, I knew that for me personally I needed to explore some other philosophies which probably have figured out things I have yet to even think to ask about. Gary Gray’s Applied Functional Science (AFS) was the first approach that peaked my interest after that point. Gary Gray arguably pioneered much of the functional training movement, with Gray Cook stating publicly he has been strongly influenced by Gary Gray’s thought process. However, getting to the point of wanting pursue learning about the AFS approach has been a 4 year journey. When I first watched videos of Gary demonstrating and discussing his thought process, I completely disregarded it because my bias at the time of what I was seeing was an awful amount of poor quality movement with no regard for what is currently considered stability, in particular with movement of the spine. But over time, I could not deny that this freedom of motion looked more useful than I had first thought. I finally bit my lip and jumped in, eventually realizing I need to at least give it a try. It was probably one of the best decisions I could have made and now has significantly influenced how I view movement and exercise prescription.

I was given the opportunity to be exposed to the AFS approach through a nine week clinical rotation at Shoreline Sport & Spine in Spring Lake, MI. There are currently 6 Fellows of Applied Functional Science™(FAFS) at this location. A FAFS has completed a 40 week fellowship through Gary Gray’s Applied Functional Science (AFS) approach. The clinicians at Shoreline have integrated AFS with a wide variety of manual therapies and other interventions which was a fantastic eclectic experience that allowed me to explore a number of ways to integrate this philosophy.

Before presenting on this topic, I must first acknowledge that these are my personal reflections on the experience, and if they are in error, they should not reflect upon the excellent clinicians at Shoreline Sport & Spine. I am certain more than one FAFS will perceive I might have missed the boat on key points, and to that, I respond that I plan to formally take a Chain Reaction™ course in the future to see what else I might have missed. Furthermore, I am commenting on but a drop in the ocean of what the AFS system entails. The “Functional Nomenclature” alone requires a 44 page manual to address simply the language and fundamental principles. That being said, here are some key things I learned from this experience:

“Drivers facilitate chain reactions throughout the body”

This was the earliest, most applicable, concept I learned from my exposure to the AFS/Chain Reaction model. It may seem like a simple statement but it is incredibly profound when broken down even a small amount. Rather than simply thinking about one joint moving on another and leaving it at that, the Chain Reaction model demands that every joint be examined from a proximal on distal and distal on proximal perspective, what are the joints above and below doing, and what planes of motion (sagital, frontal, transverse) all of the joints are moving in during any musculoskeletal action. Central to this is the concept that during movement, a driver leads the movement and the joints above and below follow that same movement, but at different speeds as they progressively move in the direction dictated by the driver. This delay in speed/timing of a bone following another bone is the Chain Reaction explanation for much of what we understand about arthrokinematics. When bones move on top of each other in multiple planes of motion in the various representations of roll, glide, spin, etc., they are doing so according to the congruencies afforded to them to allow them to follow the next bone and joint as led by the driver.

In most of our manual therapy courses, we examine relative motion of one joint on another and addresses joint movement in various planes of motion based on arthrokinematics. Traditionally, looking at joints this way was left to the manual therapy realm and not the exercise prescription realm. Oddvar Holten likely made the earliest attempt to merge the manual therapy perspective with exercise prescription with his Medical Exercise Therapy (MET – Not to be confused with muscle energy technique) which focused on utilizing various apparatuses to isolate spinal segmental levels and extremities and then focusing on patient induced movement into one or more planes of motion specific to the desired outcome determined in the manual therapy diagnosis. The Chain Reaction approach more broadly addresses this by including concepts more similar to regional interdependence and primarily using the patient’s own body and extremities to control the levels of segmental or joint emphasis through prepositioning such as: Holding on to a stable or unstable support, modifying the weight bearing surface (wedges, angles, instability), conscious prepositioning, etc. It then utilizes another joint or point of the body above or below (could be FAR above or below) to facilitate movement at the joint in the plane, or planes, desired. This approach is both a diagnosis and a treatment, which is the focus of the AFS approach. It integrates extremely well with existing manual therapy interventions, or in Gary’s opinion, independent of traditional manual therapy models, resulting in him developing his own manual therapy system specific to the AFS called Functional Soft Tissue.

Getting back to the idea of a “driver”. A driver is anything which “drives” motor behavior. This could be any part of the upper extremity, lower extremity, trunk, neck, head, eyes, sense organs, and/or even fears and beliefs. The driver itself has numerous variables which can be applied to it: Is it open or closed chain based? What action is performed? What is the direction of movement? What is the speed? What are the force demands? Etc. etc.. This is just a small list amongst many other variables, not even addressing fears and beliefs. The entire process can get very complex, very quickly, when broken down in the nomenclature which requires looking at every movement from the perspective of:

- What environment is it occurring in (given available, or specified with certain controls on stability)?

- What is the beginning position (upright, seated, kneeling, prone, supine, sidelying)?

- What exactly is the driver (hand, knee, foot, pelvis, trunk, shoulder, etc)?

- What is the triangulation (direction/target)?

- What is the action (squat, lunge, reach, pull, etc)?

- What is the ending position?

I am not qualified to go into that sort of detail, so instead I will provide a broad overview with a contemporary example. Many of us are already applying general versions of this thought process, but do not realize how far we can take it. I will use the example of a kettlebell swing.

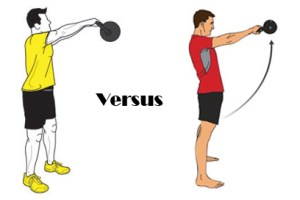

If you give a new client a kettlebell and only cue them to swing the kettlebell, they will instinctively “drive” the motion using the arms and shoulders, not their hips as you may have originally intended. They do this because you just gave them a cue which facilitates a motor pattern to accomplish the goal in the simplest way the brain understands, which is to swing their arms to swing the kettlebell, rather than to accomplish the exercise prescription goal you had intended, which was likely hip extension. If you change the cue to “Drive the hips forward”, you changed the driver of the motion to the hips, rather than the arms. Now in order to produce the force to swing the kettlebell, the individual will use a hip extension strategy. You just changed the entirety of the neuromuscular patterns utilized, even though you had the exact same exercise setup. Change the driver and the motor behavior changes. Now, if you expand this to joint by joint, things get really interesting.

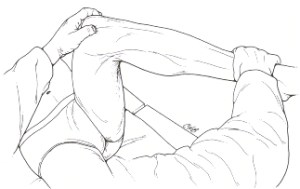

Take for example working mobility and stability of hip internal rotation. There are a handful of non-weight bearing activities which involve the femur actively or passively internally rotating on the pelvis.

We may begin with a manual therapy intervention to address mobility, then provide a mobility exercise, then a stretch, then we prescribe an exercise for stability, then we address another joint which may be associated, and we give it a mobility exercise, and a stretch, and a stabilization exercise, on and on we go. We may end up providing a large amount of exercises, all of which take time, with very specific cues and details to remember. Now with AFS, if we apply the concept of a driver along with any number of subtle changes, or “tweaks” as Gary likes to call them (the process is called “tweakology”), we can tailor a custom exercise specific to our patient needs across multiple joints with reduced need for extensive cuing and details. This can be done with fewer exercises overall because we can integrate mobility, stability, and movement across multiple joints, in multiple planes of motion, into simple exercises which require less time for the patient perform. Progression and regression are simple to teach because you are using movement patterns the client/patient already knows, you simply tweak one or two components to make changes towards the movement you want to improve.

As I am already far over my target word count for this post, I will finish with a video in which I discuss some basic strategies to emphasize hip internal rotation in weight bearing and function:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wvHEGrUs68o&w=420&h=315]

Thanks for writing about your experience Leonard. You’ve taken some good principles here and broken them down well. I admire your willingness to reengage with Gary’s concepts after initially seeing them as unsafe or unsophisticated. Function is a complex topic with numerous influences and drivers. Understanding real and relative motion certainly allows us to begin to create the reactions that we’d like to see in athletes and clients to make them more efficient and safe.

I would only continue to emphasize that Gary’s AFS approach is not intended to be unsafe, but to more deeply understand WHY the client might perform the “unsafe” maneuver, and then tweak the cause, rather than simply tweaking a “cognitive” motor pattern. He places much more emphasis on proprioceptive feedback than cortical control.

With that said, it continues to be a challenge to use the AFS approach and “tweak” in large group training situations and other scenarios when proper coaching/tweaking is not optimized.

Thank you Dave. I appreciate the great experience you and everyone at Shoreline granted me. I will admit I still cling to my beliefs about some conscious/cortical cues during the acute phases from a pain management perspective and during heavy sagital plane loading, but that may change over time :)

I don’t think of the cortex as a bad thing… As consciousness is an important regulator and is ultimately the “end point” of regulatory control. I think that subconscious proprioception could be perceived as the other end of the spectrum. The point is that most physios and trainers start AND end at the cortex.

If we found ways to start at the proprioceptor level and move towards the cortical level, would it look different? This question has begun to find a foundation in modern motor learning approaches. I can send you some papers if you’re interested.

Absolutely, always interested! Send them my way!

would you mind if we make this required reading for your classmates in advanced manual therapy? Eric and I have to lead a January lab on exercise while Dan and Corey are at CMS.

Not a problem, if you think it will be helpful I am all for it!